In 2002, Nigerian nationals who had been granted asylum in the U.S.

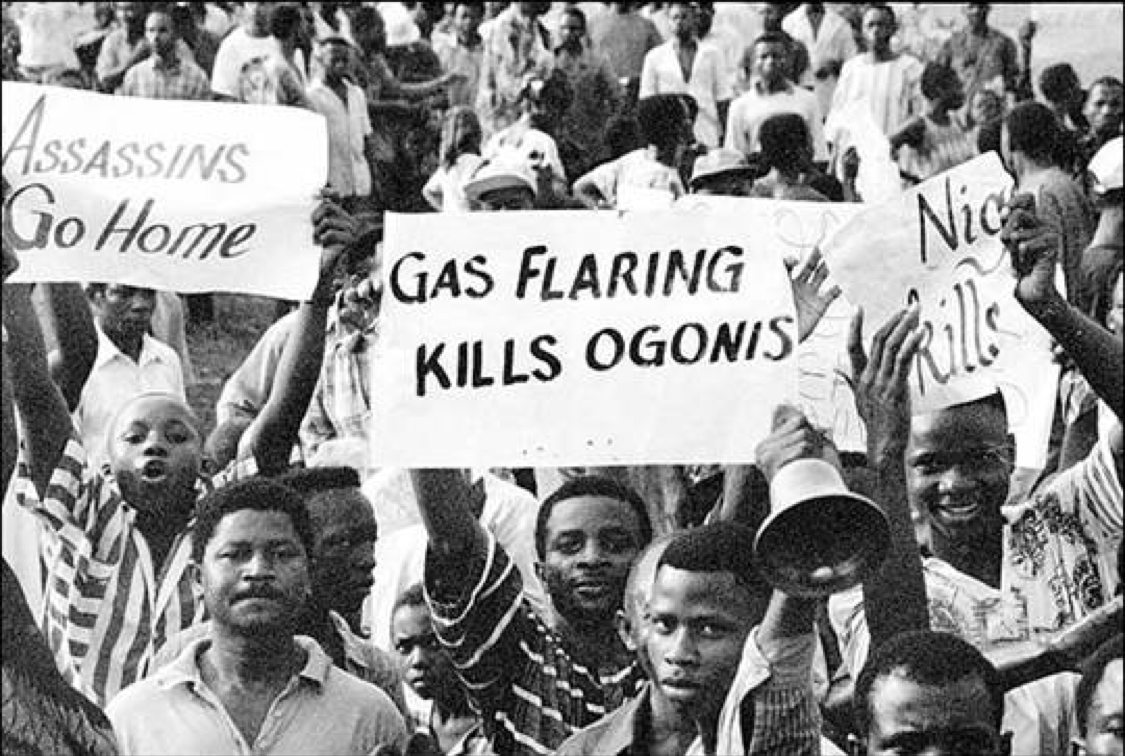

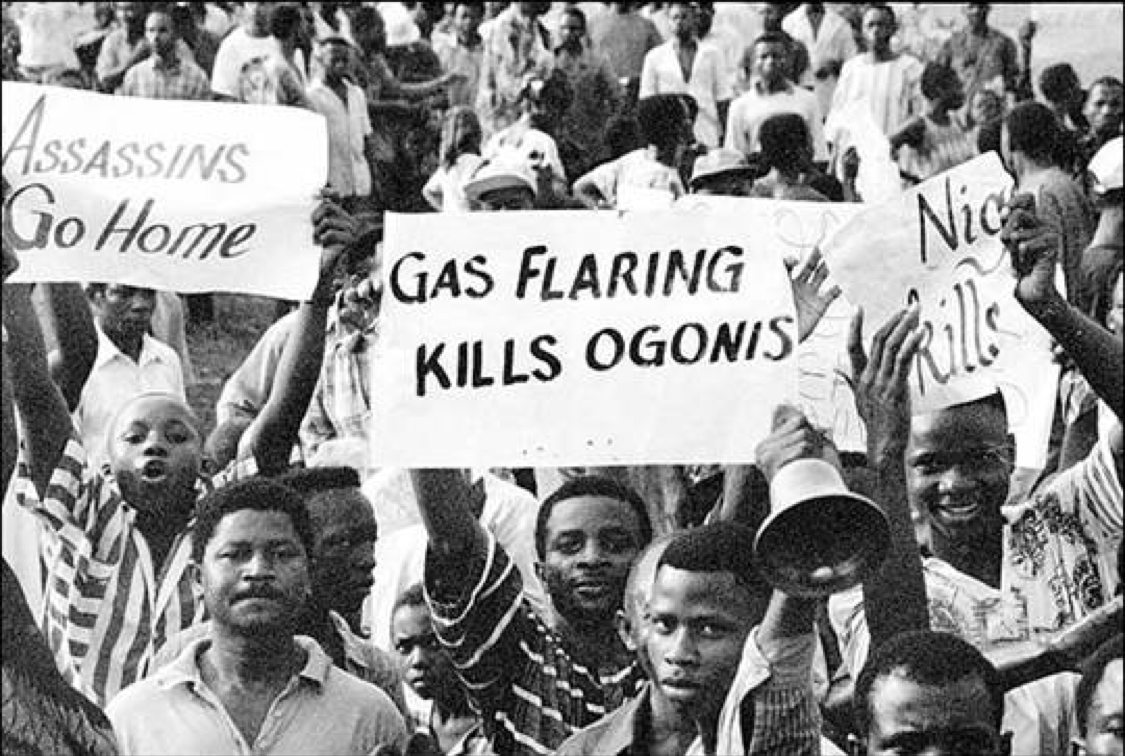

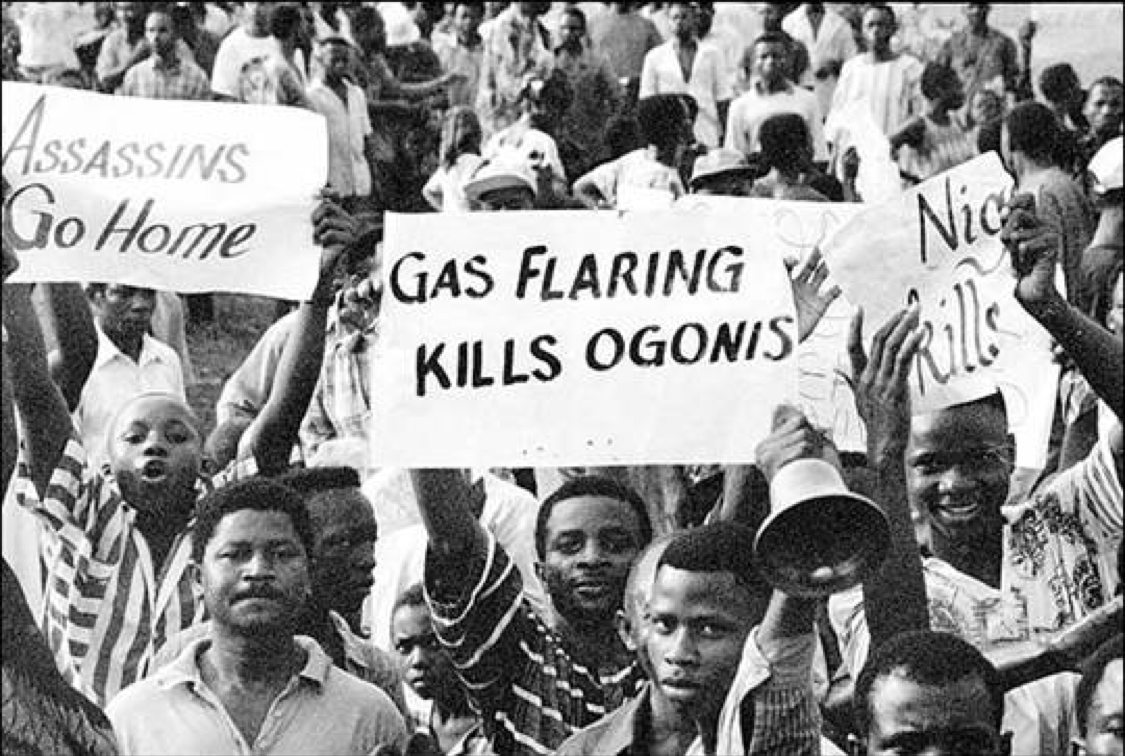

sued Dutch and British oil companies in the Southern District of New York. Specifically, the plaintiffs accused the companies of aiding and abetting the Nigerian government in carrying out environmental damage and human rights abuses. During the mid-1990’s, oil accounted for

95% of the Nigeria’s export earnings. The plaintiffs’ homeland, Ogoniland,

had been ravaged by oil production. Pipelines were constructed through farmers’ fields,

polluting the soil and destroying crops. Water in local wells had become contaminated.

Fish and

trees had begun to die. The plaintiffs’ role in

peacefully protesting oil extraction activities had made them a target of the reigning Nigerian military dictatorship. The lead plaintiff’s husband had been

extrajudicially hanged. The plaintiffs stood no chance at a fair suit in Nigeria, but they deserved a chance at relief.

The Nigerian plaintiffs sued under a statute enacted over two hundred years earlier. That statute was

28 U.S.C. §1350, better known as the Alien Tort Statute (“ATS”). It reads: “[t]he district courts shall have original jurisdiction of any civil action by an alien for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.”

Id. The statute deals with

subject matter jurisdiction: it empowers federal courts to hear a certain class of cases. It reads like a checklist. We need: (1) an alien plaintiff, (2) a tort, and (3) a violation of the law of nations or treaties.

For some time, the ATS seemed like a good way for U.S. courts to grant access to relief to foreign victims of horrific abuse—especially when those victims couldn’t find relief in their home courts. Indeed in 1980 in

Filártiga v. Peña-Irala, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals

reversed the district court’s denial of subject matter jurisdiction under the ATS. Ultimately, the Court

awarded over $10 million to a Paraguayan family whose son was kidnapped and tortured to death by a Paraguayan police officer. Since

Filártiga, ATS jurisprudence has focused on defining what types of cases are eligible for subject matter jurisdiction under the ATS. Due largely to fears over

improper interjection into foreign affairs, the statute’s scope has been gradually narrowed.

In

Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum, the case brought by the Nigerian plaintiffs, the Supreme Court denied the plaintiffs any relief in the U.S. The Court

was troubled by the idea that foreign plaintiffs were trying to sue foreign defendants for conduct that had occurred entirely outside of the United States. It resolved the case by saying that nothing in the ATS overcame the

long-held presumption that U.S. laws only apply within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States. It was too risky for

international relations, the Court reasoned, to adjudicate this kind of dispute in U.S. courts.In his opinion in

Kiobel, Chief Justice Roberts pointed out one reason to abstain from certain kinds of entanglements with international relations. Specifically, he said: “

if we say we can entertain suits by foreign plaintiffs against foreign defendants for conduct on foreign soil, there is no reason another country might not do the same to us—that is: assert jurisdiction to hear a case by a U.S. citizen against another US citizen for events occurring in the United States.”

Previously, the Presumption Against Extraterritoriality, as the prohibition on applying U.S. laws abroad is known, had been understood to pertain only to statutes that

regulate conduct. However,

Kiobel broadened the presumption to include jurisdictional statutes. After

Kiobel, the ATS was further narrowed in

Jesner v. Arab Bank, which

dictated that foreign corporations could not be held liable under the statute.

The narrowing of the ATS’s scope raises questions over whether and how the U.S. should play a role in providing justice for foreign victims of human rights abuses. The U.S. has long considered itself a defender of human rights. It has declared the promotion of human rights “

an important national interest” and the State Department states that it seeks to “hold governments accountable to their obligations under universal human rights norms.”

Id. Moreover, Judge Kaufman in

Filártiga wrote of an “

ageless dream to free all people from brutal violence.”

It is good public policy for the U.S. to care about foreign victims of human rights abuses, especially, as has frequently been the case for plaintiffs who invoke the ATS, when the U.S. has granted asylum to those people. Columbia Law professor Sarah Cleveland pointed out that adjudicating the types of disputes at issue in

Kiobel advances U.S. “

interests in deterring and punishing the world’s worst crimes, denying safe haven, compensating victims, enunciating norms, bolstering emergent democracies, and encouraging credible local rule of law institutions.” Protecting human rights reflects positively on our national morals and

is economically advantageous.

Post-

Kiobel and

Jesner, how can the U.S. best balance the goals of compensating foreign victims of human rights abuses against maintaining positive international relationships?

One solution is to determine that these objectives are largely harmonious, rather than conflicting. Congress could broaden the scope of the ATS, for example by declaring that foreign corporations may be held liable for complicity in human rights abuses abroad. Even though doing so would risk damaging relationships with countries where the abuses have taken place, it could also elevate the U.S.’s reputation among countries with which we have more meaningful or lucrative economic and social ties. The European Commission’s amicus brief in

Kiobel opined that permitting jurisdiction under the ATS would

be unlikely to encounter resistance in the international community if local remedies had been exhausted. Increased public attention to how foreign human rights abuses are handled domestically could bring the U.S.’s stated public policy concerns and the law into better alignment. Going to the press or using diplomatic channels helps raise awareness and national support for these issues. For example, public concern raised by the

United Nations Convention Against Torture contributed to the 1992 passage of the

Torture Victim Protection Act (“TVPA”), which permits suits by foreigners against foreign perpetrators of torture.

Unease about international relations implications of adjudicating foreign human rights abuses in the U.S. may be overblown altogether, since there are several important procedural backstops that keep out litigation that shouldn’t be here. Even if a U.S. court grants subject matter jurisdiction under the ATS, it cannot entertain the case unless it can also assert

personal jurisdiction over the defendant. And even if it has both personal and subject matter jurisdiction, a court may elect to dismiss a case under a doctrine called

forum non convniens if there is a more appropriate forum for the suit. A foreigner sued in the U.S. could initiate a

declaratory judgment abroad and try to get an

anti-suit injunction, which could stop the U.S. litigation from proceeding. And legislatures can build their own safeguards into statutes—for example, the previously-mentioned

TVPA requires plaintiffs to show that they have exhausted local remedies before pursuing litigation in the U.S. And that’s all before the U.S. court even reaches the case’s merits.

Even if Congress does not update the ATS, states can choose to entertain international human rights abuse claims and can procedurally make their forums more accessible to foreign plaintiffs who have been wronged. In 2015, for instance,

California extended the statute of limitations for torts where the conduct at issue would also constitute certain human rights abuses.

When the

Kiobel plaintiffs sued in federal court, they had good reason to believe that the ATS would afford them to opportunity to bring their tormentors to justice. The Supreme Court denied that that opportunity presently exists under the ATS. ATS jurisprudence has been disappointing for its reluctance to infer any intent to protect human rights abuses against foreigners on foreign soil, but its repeated encouragement to use legislative channels to do so is clear. The Supreme Court in

Kiobel, citing the TVPA, noted that

legislatures have the power to broaden courts’ ability to hear international human rights cases. It reiterated in

Jesner that “

further action from Congress” could broaden the scope of the ATS.

With respect to U.S. treatment of victims of foreign human rights abuses, Supreme Court decisions on the ATS shed light on the kind of country we are and invite us to consider what kind of country we want to be.

Suggested citation: Debbie McElwaine

, The Alien Tort Statute and Beyond: Jurisdiction for Victims of International Human Rights Abuses in U.S. Courts, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, The Issue Spotter, (Oct. 26, 2018), https://live-journal-of-law-and-public-policy.pantheonsite.io/the-alien-tort-statute-and-beyond-jurisdiction-for-victims-of-international-human-rights-abuses-in-u-s-courts/.