(Source)

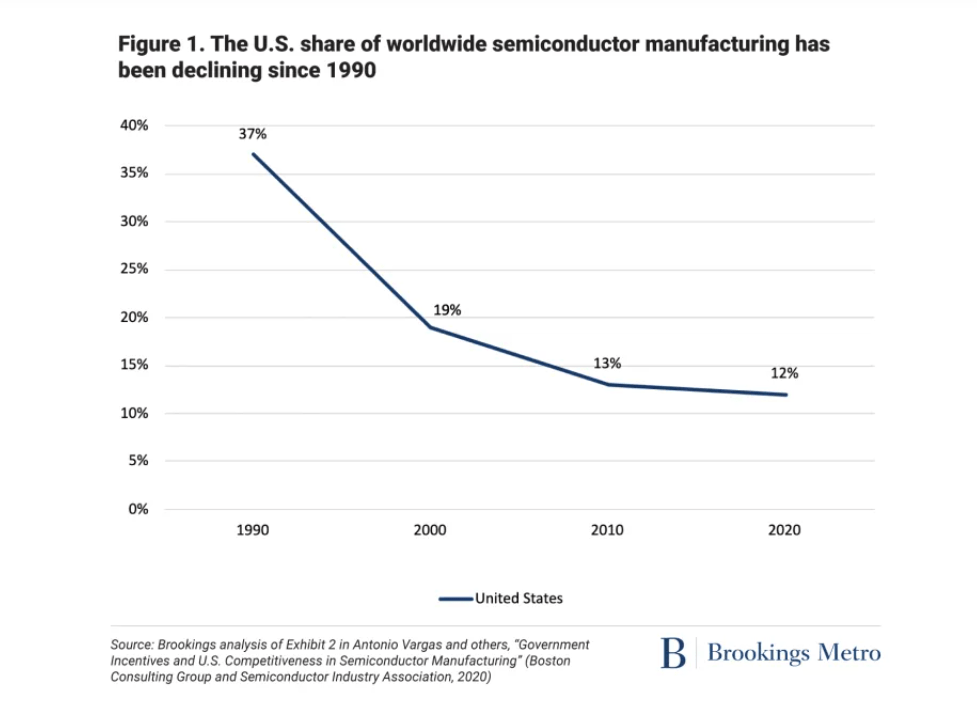

On August 9, 2022, President Biden signed into law the CHIPS and Science (CHIPS) Act, which aims to insulate the United States from future semiconductor shortages by revitalizing domestic semiconductor manufacturing capacity. Over the past thirty-five years, the U.S. share of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity decreased by more than two-thirds, falling from producing 37% of the world’s entire semiconductor output in 1990 to 12% in 2020. This drop stems from chip production moving to Asia due to higher costs in America, attributable to U.S. failures in offering large semiconductor manufacturing subsidies. More importantly, the U.S. produces none of the world’s most advanced chips. In response, the CHIPS Act allocates $39 billion, spread over five years, to boost domestic chip output, aiming to increase the U.S. share of leading-edge chip production to 20% by 2030. Currently, the CHIPS Act involves 37 projects, $272 billion in total investment, and over 36,000 new jobs.

Why should we care?

Far from a cautious fantasy, worries about chip shortages are well-founded: the world is just now leaving a global chip shortage that began during the COVID-19 pandemic and ended in 2023. However, the shortage’s effects remain. Approximately 40% of U.S. manufacturing sectors depend on chips. Unsurprisingly, the supply-chain disruption of roughly half of U.S. manufacturing sectors evoked significant economic consequences, contributing to the inflation that stubbornly persists today.

Apart from the domestic macro-economy, microchips also permeate many aspects of our daily lives. From home appliances and cars to smartphones and the internet, they affect how we communicate, work, exercise, relax, and more. Moreover, the current commercialization of Large Language Model (LLM) products is merely nascent. Consequently, we can expect microchips to only continue to increasingly embed themselves in our lives. Naturally, some experts warn of a second AI boom-fueled microchip shortage.

Where is the money going?

The CHIPS Act’s $39 billion fund allocates subsidies for semiconductor manufacturing specifically. The Act separately allocates $13 billion for semiconductor research and development. Before delving into where the money is going, some terminology and background must be explained. Companies that manufacture semiconductors are called foundries. These companies include Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) and Samsung, respectively the largest and second largest foundries in the world. Foundries manufacture semiconductors in fabrication facilities, fabs for short.

Apart from the raw base material, silica sand, which itself can be challenging to acquire, fabs require highly specialized machinery to convert the silicon dioxide found in the sand into a chip. This specialized equipment includes dicing machines, probing machines, polish and edge grinders, chemical mechanical planarization (CMP) equipment, and photolithography equipment. Moreover, fabs are also restricted to operating in extremely clean environments because even the smallest speck of foreign material can ruin a microchip.

To manufacture a microchip, foundries start with silica sand. The silicon dioxide in the sand is purified and processed into silicon wafers. Then, the wafers are coated in a light-sensitive photoresist coating. Lithography machines take the coated wafers and use light to chemically create patterns. These patterns lie underneath the now chemically altered coating, which must now be etched off. Afterward, the wafers are bombarded with ions to tune the conductive properties of the patterns. Finally, the wafer is diced into chips, which are then placed on a substrate. Finally, the microchip is ready to be placed in a device.

These processes operate on the precision of mere nanometers. The smallest microchips process that is currently commercially available is 3 nanometers. Microchips that use a 2 nanometer process are expected to arrive in 2025. In comparison, the flu virus is around 100 nanometers in diameter.

What’s wrong with the CHIPS Act?

The CHIPS Act is financially limited. The CHIPS Act invests $39 billion over 5 years in chip manufacturing, and $52 billion when combined with chip research and development. In contrast, China plans to invest $142 billion to subsidize chip manufacturing, research, and development. Surprisingly, Taiwan does not rely on direct subsidies, primarily providing subsidies through tax incentives, including a 5% deduction on annual capital expenditures (CapEx). While Taiwan’s subsidies are modest in comparison, TSMC is still expected to spend $36 billion on CapEx in 2025 alone. Moreover, TSMC’s CapEx increase is aggressive, ramping up by nearly 15% over the previous year. TSMC’s CapEx will go towards building new fabs as well as equipment, machinery, and cleanrooms. In sum, Taiwan enjoys an enormous advantage in terms of incentivizing corporate chip investment. And while the U.S. has vastly increased its subsidies for chipmakers, its investment pales in comparison to that of China’s.

Secondly, the U.S. does not have recent experience with constructing large-scale fabs. A typical Intel fab is expected to cost $10 billion and up to 5 years to complete. The enormous Intel fab in Ohio had an initial investment of $20 billion and was expected to start production by 2025. Production has already been delayed by two years.

What should be done?

The CHIPS Act should be greatly expanded in scale. More funding is needed to achieve even investment parity in a race where U.S. investment is dwarfed by that of China’s. Moreover, the U.S. ambitiously aims to produce 20% of the world’s advanced chips within the next 6 years from nothing.

Concerning the lack of building experience, the solution is more bittersweet. The lack of experience building fabs cannot be overcome easily or quickly. However, the CHIPS Act has attracted investment commitments from TSMC and Samsung to build fabs in the U.S. Learning from their experts and building a domestic repository of expertise and experience will set the tone for U.S. domestic chip manufacturing ambitions.

In sum, the CHIPS Act is a necessary start for revitalizing U.S. chip manufacturing. However, its limitations make it an uncompetitive one.

Suggested Citation: Michael Ahn, The CHIPS and Sciences Act: A First Step but Only a Step, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, The Issue Spotter (Oct. 15, 2024), http://jlpp.org/the-chips-and-science-act-baby-steps/.