(Source)

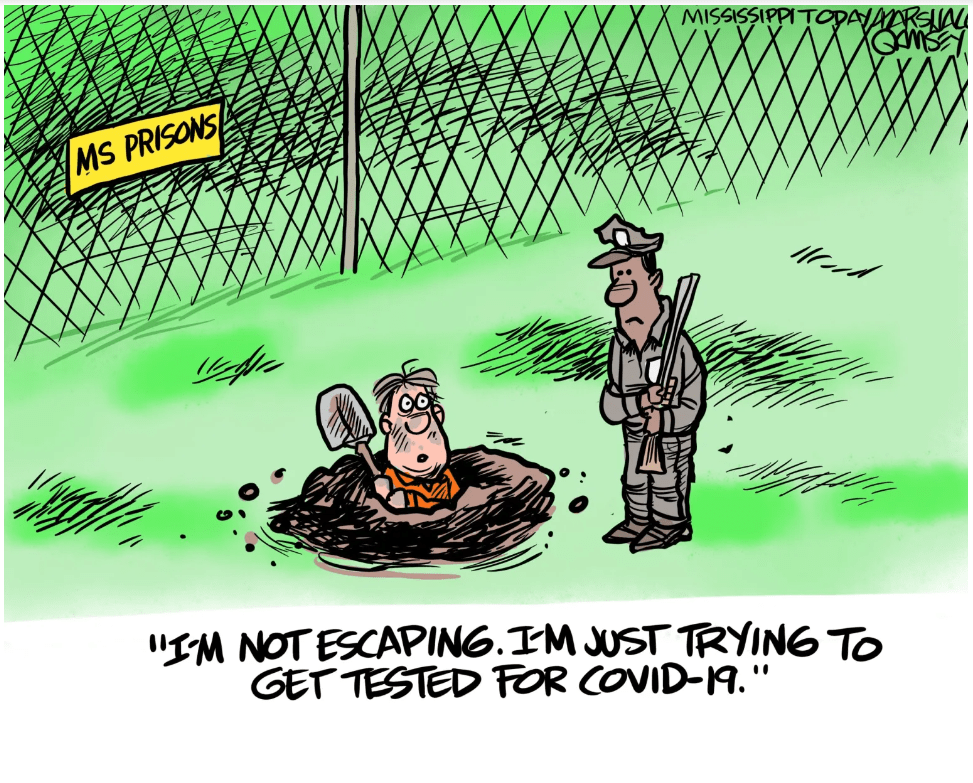

As the pandemic ramped up during 2020, leaving a deadly impact on America, it left a foreseeable and catastrophic effect on incarcerated individuals that is still felt today.

During COVID-19, there were more than half a million infections behind bars and over 3,000 deaths in prisons and jails. During the first 15 months of the pandemic, states like California, Texas, and Florida had the most COVID-19 cases, to which they experienced the most deaths among incarcerated individuals. In many other states, the high prison death rates continued into 2021, yet the exact amount is unknown because many carceral institutions did not report COVID-19 cases and deaths publicly. In fact, some jails and prisons have released critically ill individuals right before they died, so that they did not need to record nor take responsibility for their deaths. Even though it is undetermined, estimates show that the deaths due to the virus in prisons and jails are six times higher than deaths in the general population and infection rates are five times higher.

The pandemic also exacerbated punitive conditions as incarcerated individuals felt a lack of compassion from correctional officers, which caused them to feel helpless. Furthermore, the pandemic left incarcerated people struggling with their autonomy and mental health. They often felt extremely isolated, anxious, and restricted in their liberty because of the lack of social support and erasure of group activities. Due to overcrowding, inmates had to witness the spread of the virus and witness the symptoms people endured. Also, with individuals that suffered from other illnesses, fear ran rampant as they wondered if they would survive if they contracted COVID-19. With the lack of supplies and aid, necessities like high-quality masks were difficult to obtain. An incarcerated individual, Jennifer, recounts a time that a doctor recommended that they make masks out of toilet paper and gargoyle water with soap. However, this could only do so much as she was sleeping in an open dorm with 78 beds only 2 feet apart from one another. Incarcerated individuals relied on one another and their shared traumatic experiences to stay hopeful and resilient.

State and federal governments failed to implement health strategies and to reduce their population level to the amount necessary to avoid these catastrophes. In a country that locks up a larger portion of its population than any other nation in the world, overcrowding is prevalent in jails and prisons, which made social distancing impossible, left medical resources scarce, and sanitation deficient. There were widespread calls for governments to decarcerate, which were ultimately ignored. Without releasing medically vulnerable people from jails and prisons, deaths behind bars from COVID-19 easily skyrocketed.

The effect of the virus in prisons was foreseeable and warned about. Early in the pandemic, ACLU analysts partnering with researchers from Washington State University, University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Tennessee, predicted that failing to reduce prison and jail populations could lead to at least 100,000 more COVID-related deaths nationally. The prison population decreased initially solely because of the halt in admissions. However, with the exception of three states, New Jersey, California, and North Carolina, decarceration regressed as states released fewer people in 2020 than in 2019, keeping the incarcerated population vulnerable to COVID-19. American prisons also failed to effectively distribute vaccines, despite incarcerated individuals being at a heightened risk of contracting the virus. Due to their irresponsibility, these institutions created the conditions for the spread of COVID-19 to one of our most vulnerable populations: the elderly, serving harsh and targeted sentences from the war on drugs, Black and Latino people from mass incarceration, low-income people from poverty, and individuals with serious mental health concerns.

These same patterns have been prevalent before with the highly infectious influenza in 1918 and the swine flu pandemic in 2009. For example, in 2009, vaccines were also not readily available to incarcerated individuals. Seeing as how this has occurred time and time again, policymakers should evaluate remedies in order to avoid another deadly health emergency within prisons and jails.

Incarcerated individuals and justice oriented organizations have filed suit over their treatment during the pandemic, yet courts have found that providing vaccinations and using social distancing, as well as isolating people who have tested positive for COVID-19, is sufficient protocol for prisons and jails. However, more needs to be done in addition to current guidelines to improve health prospects and prevent another widespread fatality event within criminal justice institutions.

For starters, in addition to pushing for decarceration, there needs to be efforts made to improve sanitation within these institutions. There needs to be an increase in personal hygiene products, more space, and an investment in healthcare to help all incarcerated individuals especially those with poor physical and/or mental health. During the pandemic, some facilities did not provide hand sanitizers because the high-alcohol levels could be considered as contraband and did not provide masks unless someone was exposed to another person who tested positive for COVID-19. There needs to be immediate and wide rollout of vaccines to the prison populations whenever there are health emergencies. Halting activities like group therapy and religious activities in facilities to promote social distancing, however, has a negative impact on the mental health of prisoners. When group activities need to be halted for safety measures, there needs to be programs in place to maintain stable mental health, for example, providing one on one counseling or telehealth counseling. Additionally, there needs to be empathetic training given to correctional staff to ensure there is not a lack of compassion from their end leaving inmates feeling dehumanized as well as a mandated following of medically ethical principles.

While many prisons and jails across the country failed to act to prevent the spread of the virus among their incarcerated population, the Franklin County Sheriff’s Office in Massachusetts sets an example as one of the first jails to provide correctional populations with access to all medications to treat opioid use disorder during the pandemic as well as implementing mitigation policies. The model included health care and social worker staff meeting every day to make health care to do lists for the inmate, placing incarcerated individuals in front of the telehealth computer for engagement with caseworkers and clinicians. There was collaboration with organizations to secure additional sober housing beds and postrelease re-entry programs utilized telehealth options including telehealth groups to access community treatment. FSCO’s COVID-19 mitigation measures were highly effective as they did not have any COVID-19 outbreaks in their incarcerated population or their staff. The FCSO’s program is an example of how advocated solutions have worked and using mitigation strategies early help to save lives. This should be applied broadly to prisons and jails nationwide.

Suggested Citation: Marieya Jagroop, Surviving COVID-19: The Treatment of Incarcerated Individuals During the Pandemic, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, The Issue Spotter, (2024), https://jlpp.org/surviving-covid-19-the-treatment-of-incarcerated-individuals-during-the-pandemic/.