(Source)

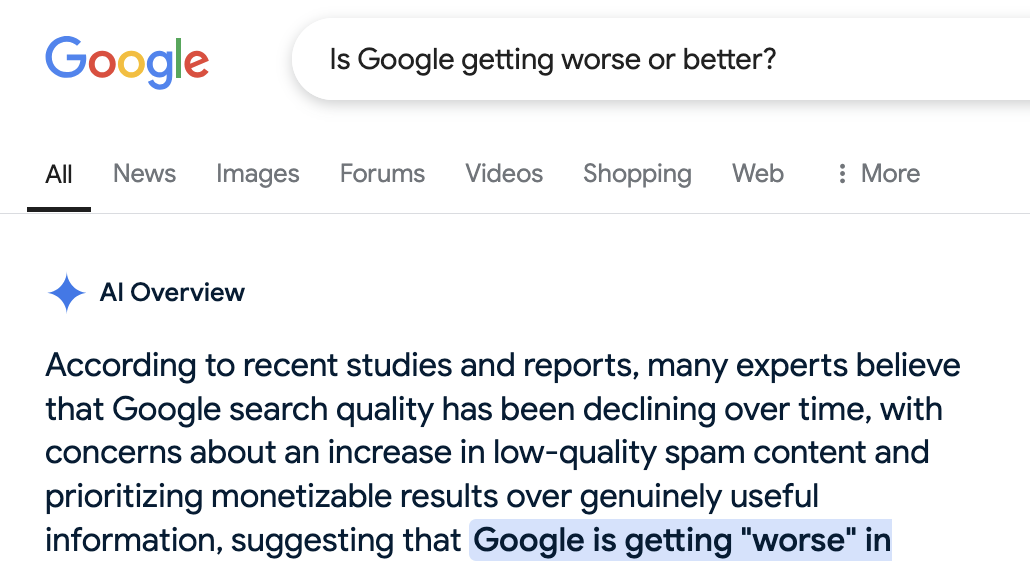

One of the greatest technological marvels of the 21st century was the fact that anyone could find a reliable answer to any question simply by typing a few words into a device that could be carried in their pocket. However, Google’s monopolization of internet search results may cause this era to come to an end, with growing concerns that a sharp decrease in Google’s quality is ruining our ability to search for information online. A 2024 study finds that Google search is not delivering the same results that it once did, with relevant, useful content few and far between pages of low-quality, repetitive, AI-generated junk articles. Google does not dispute that its product review search has worsened, but argues that despite this study’s results, their own product is still of significantly higher quality than other search engines. This illustrates a greater issue: despite Google’s decrease in quality, it is still the most popular search engine around, and its lack of competitors is harming our ability to find relevant information. Because so many of us have relied on Google for decades as a reliable way to find accurate information, the worsening of Google search has larger implications for our ability to conduct accurate research, dispute misinformation online, and consumers’ ability to find honest, non-sponsored information about products. The federal government has attempted to address Google’s dominance over search in the past, but must further tailor its newer antitrust strategies if it intends to effectively curb Google’s monopoly over internet searches.

Many attribute Google’s deterioration to Search Engine Optimization (“SEO”). In Google’s own guide to SEO, the company advises website developers to use specific optimization strategies to maximize their likelihood of popping up in a Google search. These include writing web pages with search terms in mind, creating subheadings that incorporate keywords, and linking to relevant sources. In practice, these methods flood Google’s first few pages of search results with junk sites, listicles, and AI generated articles that repeat similar phrases and cram content into unnecessary headings to rank higher in Google search. Many developers’ sites (heavily optimized themselves) warn that without SEO for Google specifically, a site’s rankings in search results will drop and the site will become less visible to users. An industry has emerged around optimizing websites for Google search, where SEO experts advertise their ability to help businesses appear earlier in search results. A failure to optimize for Google can be disastrous for a site. HouseFresh, an independent review site of air purifiers, was forced to lay off most of its team after an update to Google’s algorithm drastically reduced its traffic from search results, directing consumers to sites that had clearly not tested the products.

Although Google has taken steps to address spam search results, some tech experts worry that Google’s market dominance and continuing profits mean that the company has no incentive to devote resources towards improving its user experience. In fact, subpar results may be beneficial to the company’s bottom line. Google has already been subjected to several antitrust cases by the Department of Justice (“DOJ”). A 2020 action by the DOJ alleged Google violated Section 2 of the Sherman Act by entering exclusive contracts with companies like Verizon, Samsung, Apple, and T-Mobile to make its search engine the default on devices. A 2023 action, also based in the Sherman Act, accused Google of eliminating competition in digital advertising by buying up competing advertising products. Email threads uncovered by these lawsuits highlighted conversations between executives regarding the functionality and quality of Google search, most notably that worse search results would increase the time spent viewing ads on Google’s home page.

In both suits, the DOJ employed novel antitrust theories to better address digital monopolies. The federal government has had to make significant changes to the way it approaches antitrust enforcement in the age of Big Tech. Free web services and social media sites, like Amazon and Facebook, cost nothing to consumers and advertise themselves as platforms for users, buyers, and sellers, making it difficult to bring traditional antitrust actions against them. “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,” a law review article written by former FTC chair Lina Khan in 2017, proposed a new approach to enforcement actions: viewing the platform from both the buyer and seller sides. Amazon, her prime example, is a service that is free to use for consumers. However, Amazon is so prevalent in e-commerce that sellers are forced to sell on the platform to be visible and pay Amazon’s listing fees, raising their own prices and in turn harming consumers. It is clear that by attempting to address harms to advertisers using Google services, the DOJ is attempting to employ a similar strategy against Google.

These strategies have produced tangible results in recent litigation: April 17, 2025, Google was ruled to be an illegal monopoly, and was recently required by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to start sharing certain search data with competitors. Although touted as a victory for the Department of Justice, many were concerned that Google’s lawsuit did not have enough “bite” to have real consequences for the company. Proponents of antitrust regulation feel that the new requirements will do little to address Google’s monopoly over the search engine market. Google was not required to divest from major properties such as Chrome, share parts of its algorithm or significant amounts of search data, or cease making exclusive agreements with other companies.

This lack of sufficient remedies may reveal holes in the federal government’s newer approach to antitrust: although focusing on advertisers and default browser agreements will chip away at Google’s monopoly power, recent court-ordered remedies will not materially improve the experiences of consumers or the quality of Google’s results. Google’s dominance allows it to decrease the quality of its search with few ramifications, but web searches (which are free to use) are generally not considered “markets” by courts. This view of tech platforms as “free services” is outdated by decades, and the federal government must further tailor its modern antitrust strategies to address the root of consumer harm. Instead of attempting to circumvent traditional antitrust limitations by benefitting sellers and advertisers, newer antitrust legislation must acknowledge that in the digital age, their use has a material cost—consumers’ data, time, and privacy. Google can track and provide everything from YouTube watch history to Google Maps location data to advertisers, and consumers are often forced to navigate through pages of affiliate links and sponsored content every time they hit “enter” on a Google search. If given the specific focus of search quality, courts may be more open to addressing Google’s monopoly through measures that effectively increase competition and improve the quality of other sites, such as forcing Google to syndicate search results, divest from its Chrome web browser, or share additional search data that can be used to improve web browsers of rivals.

Suggested Citation: Ria Panchal, Google’s Antitrust Paradox: Can Modern Antitrust Principles Fix Google Search?, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, The Issue Spotter, (Dec. 3, 2025), https://publications.lawschool.cornell.edu/jlpp/2025/12/03/googles-antitrust-paradox-can-modern-antitrust-principles-fix-google-search/.

About the Author