(1) where officers must provide emergency assistance to an occupant of the home,

(2) to engage in “hot pursuit” of a fleeing suspect after the commission of a felony,

(3) to enter a burning building to put out a fire and investigate its cause, or

(4) to prevent the imminent destruction of evidence.[2]

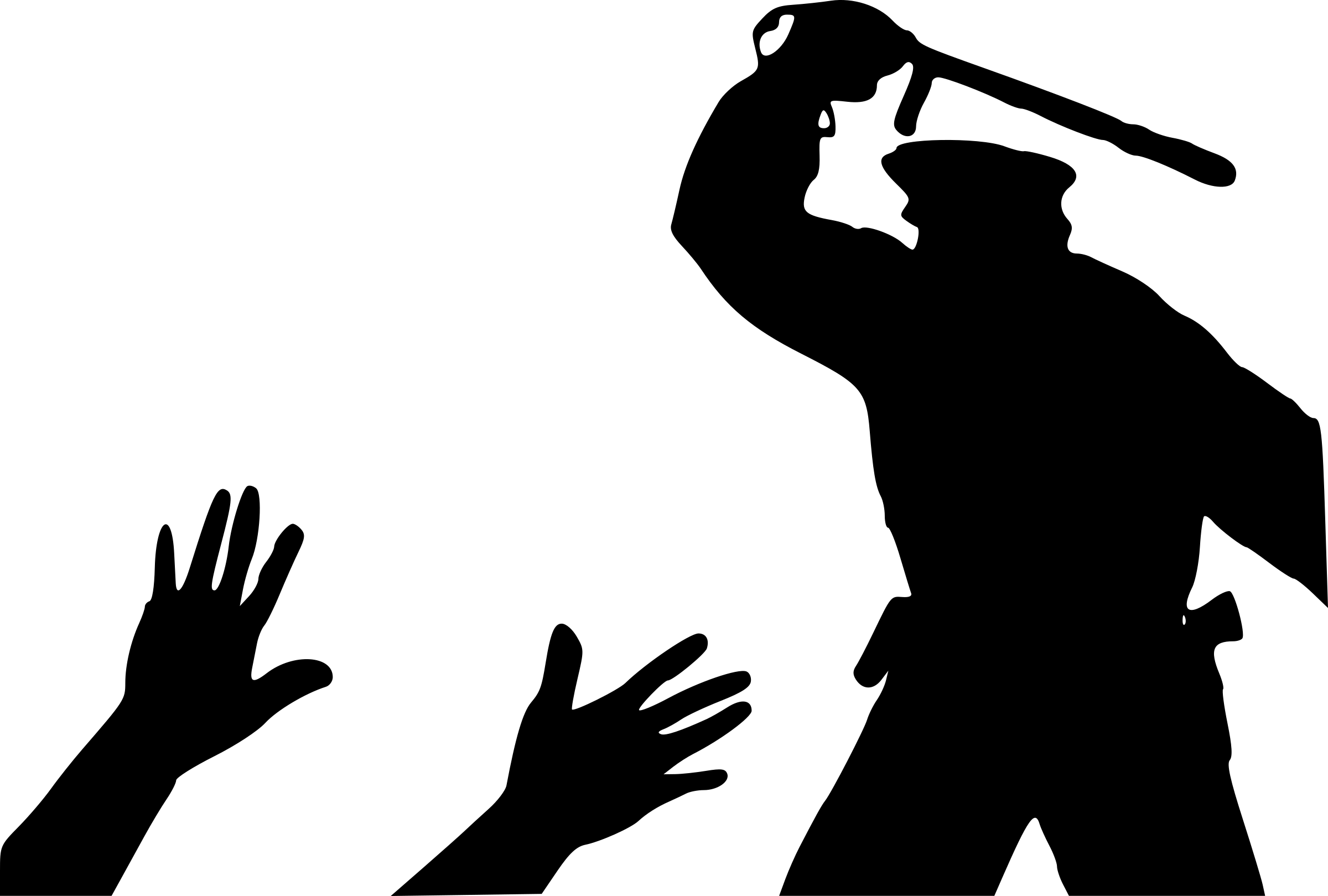

Importantly, a warrantless arrest at home is not justified where there is no showing of exigent circumstances leading to the arrest itself; that is, if the police created the alleged exigent circumstances, the exception could not apply. Accordingly, existing case law establishes that warrantless arrests—in the absence of exigent circumstances and clear consent—violate the Fourth Amendment. The students’ encounter with the police originated with a noncriminal noise complaint. None of those “exigent circumstances” appear in the video or are alleged by the police, there appears to be a clear answer to our question: It was not legal for the police to enter the student apartment and it was not legal to effectuate the arrests under the circumstances. That leads us to the second issue regarding the use of force. In Graham v. Connor, the Supreme Court recognizes the long-standing right of police officers to use reasonable force (or threat of force) to arrest individuals. That means that “not every push or shove, even if it may seem unnecessary later,” by the police is excessive and unconstitutional. Instead, the Court articulates a careful balance of the “nature and quality of the intrusion on the individual’s Fourth Amendment interests” against the countervailing governmental interests at stake. Consequently, all claims of excessive police force are subject to this analysis. The Graham standard is one of objective reasonableness, without consideration of a police officer’s subjective intent or motivation (whether malicious or in good faith). The Graham standard measures this from the perspective of a reasonable police officer on the scene based on the totality of circumstances. That means “20/20 hindsight” is irrelevant; rather, taking into account that circumstances are “often tense, uncertain and rapidly evolving.” Ultimately, in determining reasonableness courts look to the so-called “Graham Factors”, including:(1) the severity of the crime at issue,

(2) whether the suspect poses an immediate threat to the safety of the officers or others, and

(3) whether the suspect is actively resisting arrest or attempting to evade arrest by flight.

In McNally v. Eve, a federal court applied this analysis to facts nearly analogous to this case. There, police were called to investigate a noise violation at a house party, finding the host wearing only a bathrobe. The host refused the police entrance without a warrant and attempted to turn away when threatened with arrest. The host was then tasered, brought to the ground, and arrested for obstruction of justice. The court found that violating the noise ordinance—and even the alleged crime of obstruction—was of minor severity; that the host, speaking calmly and clearly unarmed, posed no threat to the officer nor anyone else; and, that the host never resisted arrest, nor attempted to flee (even by turning away). Accordingly, the court held that the evidence was sufficient to find the officer’s conduct objectively unreasonable under the circumstances, thus, the conduct was excessive and in violation of the Fourth Amendment. Based on the video evidence and existing law, it’s difficult to find the officers’ conduct, in this case, reasonable. As in McNally, the police responded to a noncriminal noise complaint and were refused entrance without a warrant by the unarmed students who made little or no attempt to resist or flee; then the students were tasered and repeatedly beaten with batons while clearly in police custody. (See “00:34–00:37” in the video.) This is particularly significant considering that a suspect, being held on the ground and in police custody, cannot objectively be considered a threat requiring additional force. Hence, under a Graham analysis, the officers’ conduct is almost certainly objectively unreasonable based on the circumstances, and therefore, unconstitutional. So, the bottom line: the officers’ conduct in the video certainly appear to be illegal. [1] 5 Am. Jur. 2d Arrest §§ 99, 102 (2015). [2] 3A Charles Alan Wright, Andrew D. Leipold, Peter J. Henning, & Sarah N. Welling, Federal Practice and Procedure: Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure § 678 (4th ed. 2010).