(Source)

Today, more fish are farmed worldwide than are caught in the wild with demand only increasing year over year. Economic projections predict global seafood consumption to nearly double in the next quarter century. Future growth in aquaculture will lie offshore, with inshore aquaculture remaining largely stagnant. In contrast, American inshore aquaculture projects to continue growing while American offshore aquaculture is currently stymied by inefficient and unclear regulations. With respect to demand, Americans are heavily dependent on imports for their seafood, importing around 80% of what they consume, contributing to an annual trade deficit of over $20 billion.

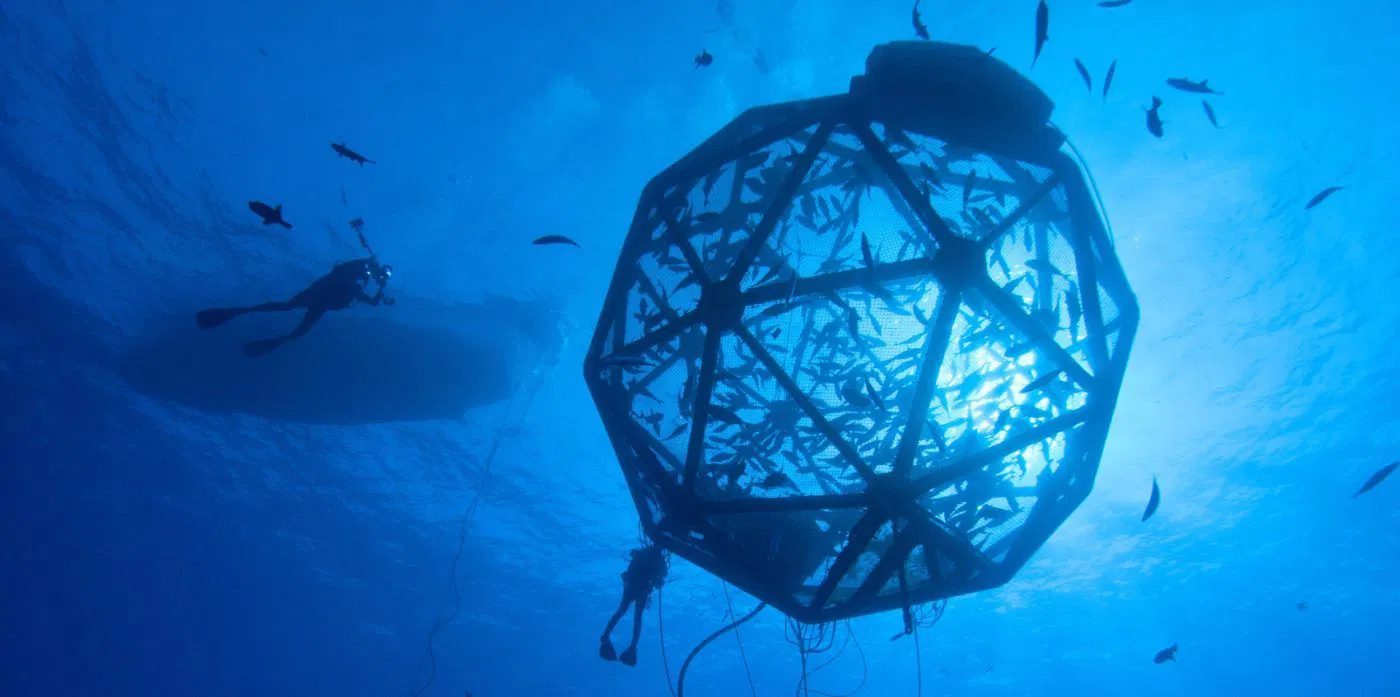

Aquaculture is the breeding, raising, and harvesting of finfish, shellfish, and aquatic plants. Offshore aquaculture operates in exposed ocean waters, while inshore aquaculture occurs nearer to the coast or inland. Compared to red meat production, aquaculture produces better nutrition with superior cost efficiency in protein produced per pound of feed. However, aquaculture also has significant environmental drawbacks. Aquaculture discharges polluted effluent created by uneaten feed and waste, cannibalizes wild fish stocks used to produce feed, raises the risk of disease by concentrating fish populations, and endangers nearby ecosystems due to invasive escapees.

Currently, American aquacultural regulation is dated, unclear, and uncompetitive. This regulatory hodgepodge can be gleaned from the permitting process for aquaculture operations. Permitting depends on the siting of the aquaculture operation, the discharge of material into the waters of the United States, the discharge of pollutants, feed, nutrients, pharmaceuticals, or other substances into the waters of the United States, and the taking or harvesting of Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA) managed species. Once these factors are known, several permits will then need to be filed to the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). These permissions are granted under four separate federal statutes and contemplate state regulations. Lastly, the USACE promotes general permits to “streamline” the permitting process, but up to three different permits may need to be submitted depending on the species being farmed. All told, at least six different agencies claim regulatory authority over aquaculture generally, with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) claiming sole authority over offshore aquaculture specifically.

The case law only adds to the confusion. In Gulf Fisherman’s Association v. National Marine Fisheries Service, the court held that the NMFS did not have authority under the MSA to regulate offshore aquaculture. Consequently, that regulatory authority is held by individual regional councils, each capable of prescribing differing or conflicting regulations. Overall, the decentralization of regulatory authority over offshore aquaculture presents a nightmare for both current farmers and prospective farmers to navigate.

Naturally, Congressional legislation reforming the current regulatory regime would be well-suited to building a streamlined, centralized solution, but Congress has failed to do exactly that for the past twenty years. Meanwhile, competitive seafood exporters, unsurprisingly, have model competitive regulatory regimes: Norway has a “streamlined one-stop process… within a comprehensive regulatory framework” that promotes industry growth. On the other hand, American regulatory reform has been a five-time nonstarter, failing to build consensus and leaving in place a suffocating regulatory regime.

Opponents of offshore aquaculture argue that it carries significant risks to the environment, that American aquaculture producers lack international competitiveness, and that offshore aquaculture would endanger the livelihoods of fishers. On the other hand, proponents of offshore aquaculture argue that the environmental impact would be significantly mitigated because deeper waters are more capable of diffusing the released effluent. Consequently, regulatory reform requires greater consensus, which can be achieved by defusing some of these concerns.

Differentiating between unfed and fed aquaculture is likely to help build that consensus. A quick look at the average American seafood diet reveals that, by weight, the annual split between finfish and shellfish is roughly 65% to 35%, making shellfish a significant driver of American seafood demand. Robust domestic demand should help alleviate concerns about the international competitiveness of American shellfish because American shellfish would not need to win in overseas markets, merely their own. On the supply side, shellfish make up 8% of American aquaculture production by weight. However, by value, shellfish’s contribution rises to roughly 25%. In terms of American marine aquaculture alone, which includes offshore aquaculture, this share balloons to almost 83%. Aquatic plant aquaculture has also been on the rise. In Alaska, home to America’s largest seaweed farms, the seaweed crop tripled between 2017 and 2019. Consequently, American seafood consumption and production patterns, which favor offshore shellfish and aquatic plant aquaculture, emphasize a preference gap between offshore unfed and fed aquaculture.

Distinguishing between fed and unfed aquaculture also capitalizes on their differing environmental cost profiles. Unfed aquaculture has a distinctly lesser environmental footprint than fed aquaculture. Fed aquaculture requires feeding finfish a diet of fishmeal, fish oil, plants, and animal trimmings. In contrast, unfed aquaculture operations cultivating shellfish and aquatic plants use nutrients in the water and sunlight, respectively. Furthermore, seaweed, in particular, enhances biodiversity, absorbs carbon dioxide, and mitigates ocean acidification. Consequently, focusing on unfed aquaculture significantly sidesteps environmental concerns regarding offshore aquaculture.

Overall, focusing initially on unfed offshore aquaculture reveals an easier path to regulatory reform because it aligns better with America’s seafood tastes, production, and environmental interests.

The MSA is almost fifty years old. It is time to cut bait.

Suggested Citation: Michael Ahn, American Offshore Aquaculture: Cutting Bait, Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, The Issue Spotter (Mar. 19, 2025), http://jlpp.org/blogzine/american-offshore-aquaculture-cutting-bait/.