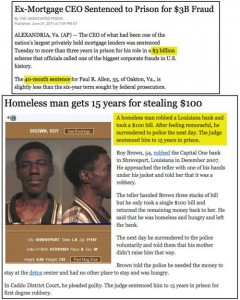

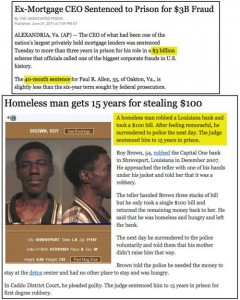

If you’ve poked around the internet the past month, you might have come across the image below. The meme juxtaposes two news articles to highlight the questionable retributive values behind American criminal law. But some people are crying

hoax about this viral phenomenon—are they correct?

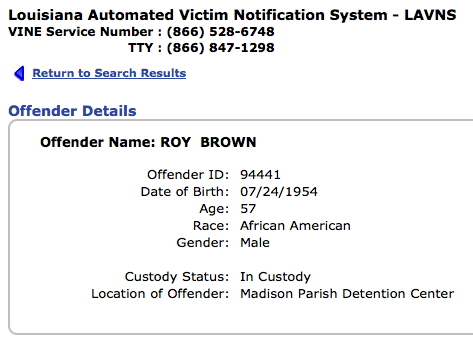

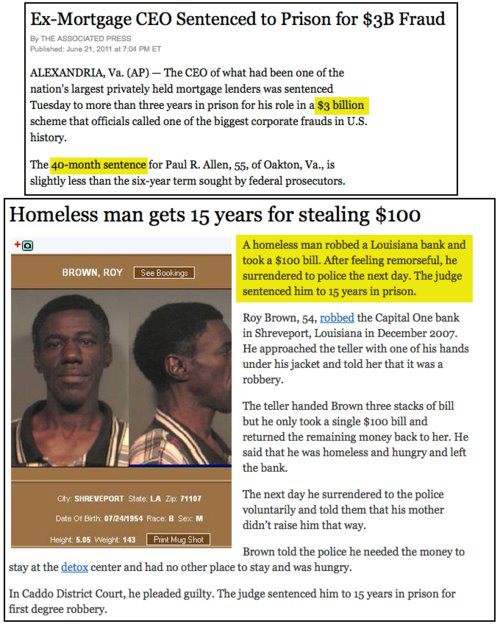

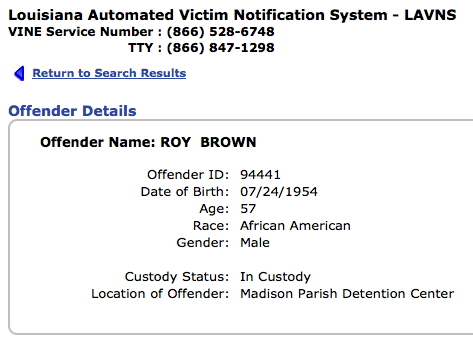

Meet Paul R. Allen, the former CEO of one of the nation’s largest privately held mortgage lenders, Taylor, Bean & Whitaker, which collapsed in 2009 due to a massive $3 billion fraud scheme which resulted in 2,000 employees losing their jobs. Paul was sentenced to 40 months in prison for his role in the scheme. Now meet Roy Brown, a homeless resident of Shreveport, Louisiana, who robbed a bank for $100 because he was hungry—only to remorsefully turn himself in the very next day. Roy was sentenced to 15 years in prison for first-degree robbery. I came across this image of the two of them sometime last year, long before the Occupy Wall Street movement made it viral again. At the time, I refused to believe Roy Brown was sentenced to 15 years for stealing $100—which he later voluntarily surrendered. When the image resurfaced again last month, I dug a little deeper into Roy’s story, as Paul Allen’s story was much easier to verify. Through some internet sleuthing, I found out that

Roy Brown is indeed incarcerated at Madison Parish Detention Center in Louisiana:

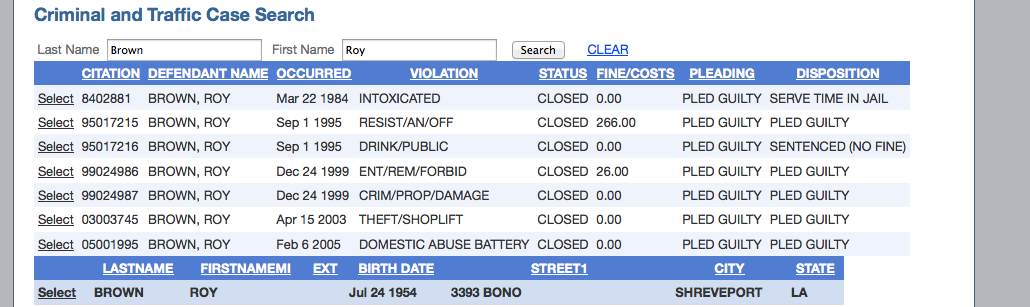

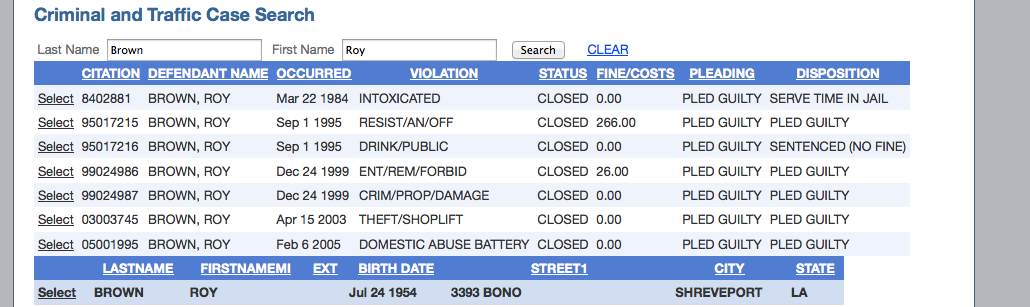

I was also able to

obtain a list of Roy Brown’s criminal offenses, all of which are part of the public record:

The original story was written by

KTBS in Shreveport, Louisiana and can be found

here. Other diligent bloggers have looked into the story and even contacted KTBS, which

has stood by the story’s authenticity.

Now that we know

Roy Brown isn’t a hoax, how can we explain the absurdity of his sentence? As usual, the internet is full of skeptics and naysayers who are quick to point out Roy’s prior offenses. Some of them even consider the 15-year-sentence

generous. If

Louisiana’s three strikes law was at play, Brown could have faced life in prison. Roy’s sentence for first-degree robbery alone could have been

anywhere from 3 years to 40 years.

Internet skeptics are also quick to point out that Paul R. Allen wasn’t instrumental in the $3 billion fraud scheme. These skeptics are the problem and reason behind the outcry about these two men. Do we

really believe that the fact Roy Brown “seemed armed” to the teller is decisive—no matter what the difference is between $100 and $3 billion? No matter whether or not there were mitigating factors at play—hunger, homelessness, and voluntary surrender?

The huge difference in the punishment for these crimes is due, at least in part, to simple human psychology. In

The Life You Can Save, Australian philosopher

Peter Singer explored why millions continue to die of preventable disease, malnutrition, and starvation, despite the arsenal of wealth available to solve all of these problems. He attributed it to

diffusion of responsibility and

cognitive dissonance—in one of the book’s examples, he asks you, the reader, to imagine walking briskly to work in a wool suit. You pass a toddler in a shallow pond, and the toddler appears to be drowning. No one else is in the vicinity. In that moment, almost anyone would run into the pond, save the child, and happily ruin the wool suit and arrive late to work. Then Singer reminds readers: At the same time you are walking to work in a suit, somewhere else in our world, a child is dying of hunger. In fact,

Bread for the World estimates, a child

dies of hunger every five seconds. Sure, you and I can’t save every single one of those children on our own. But the shocking part is that

chances are high that you and I have never even tried to save one of them.

We can

feel robbery. We can feel someone taking $100 out of our hand and we can picture the teller terrified and faced with what appears to be a gun. We have a lot of trouble

feeling an elaborate, unfamiliar $3 billion tax scheme, where a simple click of a mouse can imperceptibly bankrupt someone and the “crook” sits harmlessly at a mahogany desk.

Empathy and action have a lot to do with visibility. As a result, we often fail to empathize with the little people who suffer from the big schemes: the employee with dashed hopes of retirement, the mother who fruitlessly cut corners for her child’s education, the family who must now depend upon food stamps.

This dependency we have on

feeling is at the root of refusing to admit that these stories represent an injustice. Our criminal system is littered with sweeping laws enacted after public outcries (e.g. the

AEDPA enacted in the wake of the Oklahoma City Bombing), but what that system needs now is reform from the head, not from the heart.

Note: There was a typo in the first version of this post indicating Paul R. Allen was sentenced to 3 months in prison. It has been corrected to reflect the sentence was 40 months. I sincerely apologize for the error. -Suzy Marinkovich

Meet Paul R. Allen, the former CEO of one of the nation’s largest privately held mortgage lenders, Taylor, Bean & Whitaker, which collapsed in 2009 due to a massive $3 billion fraud scheme which resulted in 2,000 employees losing their jobs. Paul was sentenced to 40 months in prison for his role in the scheme. Now meet Roy Brown, a homeless resident of Shreveport, Louisiana, who robbed a bank for $100 because he was hungry—only to remorsefully turn himself in the very next day. Roy was sentenced to 15 years in prison for first-degree robbery. I came across this image of the two of them sometime last year, long before the Occupy Wall Street movement made it viral again. At the time, I refused to believe Roy Brown was sentenced to 15 years for stealing $100—which he later voluntarily surrendered. When the image resurfaced again last month, I dug a little deeper into Roy’s story, as Paul Allen’s story was much easier to verify. Through some internet sleuthing, I found out that Roy Brown is indeed incarcerated at Madison Parish Detention Center in Louisiana:

Meet Paul R. Allen, the former CEO of one of the nation’s largest privately held mortgage lenders, Taylor, Bean & Whitaker, which collapsed in 2009 due to a massive $3 billion fraud scheme which resulted in 2,000 employees losing their jobs. Paul was sentenced to 40 months in prison for his role in the scheme. Now meet Roy Brown, a homeless resident of Shreveport, Louisiana, who robbed a bank for $100 because he was hungry—only to remorsefully turn himself in the very next day. Roy was sentenced to 15 years in prison for first-degree robbery. I came across this image of the two of them sometime last year, long before the Occupy Wall Street movement made it viral again. At the time, I refused to believe Roy Brown was sentenced to 15 years for stealing $100—which he later voluntarily surrendered. When the image resurfaced again last month, I dug a little deeper into Roy’s story, as Paul Allen’s story was much easier to verify. Through some internet sleuthing, I found out that Roy Brown is indeed incarcerated at Madison Parish Detention Center in Louisiana:

I was also able to obtain a list of Roy Brown’s criminal offenses, all of which are part of the public record:

I was also able to obtain a list of Roy Brown’s criminal offenses, all of which are part of the public record:

The original story was written by KTBS in Shreveport, Louisiana and can be found here. Other diligent bloggers have looked into the story and even contacted KTBS, which has stood by the story’s authenticity.

Now that we know Roy Brown isn’t a hoax, how can we explain the absurdity of his sentence? As usual, the internet is full of skeptics and naysayers who are quick to point out Roy’s prior offenses. Some of them even consider the 15-year-sentence generous. If Louisiana’s three strikes law was at play, Brown could have faced life in prison. Roy’s sentence for first-degree robbery alone could have been anywhere from 3 years to 40 years.

Internet skeptics are also quick to point out that Paul R. Allen wasn’t instrumental in the $3 billion fraud scheme. These skeptics are the problem and reason behind the outcry about these two men. Do we really believe that the fact Roy Brown “seemed armed” to the teller is decisive—no matter what the difference is between $100 and $3 billion? No matter whether or not there were mitigating factors at play—hunger, homelessness, and voluntary surrender?

The huge difference in the punishment for these crimes is due, at least in part, to simple human psychology. In The Life You Can Save, Australian philosopher Peter Singer explored why millions continue to die of preventable disease, malnutrition, and starvation, despite the arsenal of wealth available to solve all of these problems. He attributed it to diffusion of responsibility and cognitive dissonance—in one of the book’s examples, he asks you, the reader, to imagine walking briskly to work in a wool suit. You pass a toddler in a shallow pond, and the toddler appears to be drowning. No one else is in the vicinity. In that moment, almost anyone would run into the pond, save the child, and happily ruin the wool suit and arrive late to work. Then Singer reminds readers: At the same time you are walking to work in a suit, somewhere else in our world, a child is dying of hunger. In fact, Bread for the World estimates, a child dies of hunger every five seconds. Sure, you and I can’t save every single one of those children on our own. But the shocking part is that chances are high that you and I have never even tried to save one of them.

We can feel robbery. We can feel someone taking $100 out of our hand and we can picture the teller terrified and faced with what appears to be a gun. We have a lot of trouble feeling an elaborate, unfamiliar $3 billion tax scheme, where a simple click of a mouse can imperceptibly bankrupt someone and the “crook” sits harmlessly at a mahogany desk.

Empathy and action have a lot to do with visibility. As a result, we often fail to empathize with the little people who suffer from the big schemes: the employee with dashed hopes of retirement, the mother who fruitlessly cut corners for her child’s education, the family who must now depend upon food stamps.

This dependency we have on feeling is at the root of refusing to admit that these stories represent an injustice. Our criminal system is littered with sweeping laws enacted after public outcries (e.g. the AEDPA enacted in the wake of the Oklahoma City Bombing), but what that system needs now is reform from the head, not from the heart.

Note: There was a typo in the first version of this post indicating Paul R. Allen was sentenced to 3 months in prison. It has been corrected to reflect the sentence was 40 months. I sincerely apologize for the error. -Suzy Marinkovich

The original story was written by KTBS in Shreveport, Louisiana and can be found here. Other diligent bloggers have looked into the story and even contacted KTBS, which has stood by the story’s authenticity.

Now that we know Roy Brown isn’t a hoax, how can we explain the absurdity of his sentence? As usual, the internet is full of skeptics and naysayers who are quick to point out Roy’s prior offenses. Some of them even consider the 15-year-sentence generous. If Louisiana’s three strikes law was at play, Brown could have faced life in prison. Roy’s sentence for first-degree robbery alone could have been anywhere from 3 years to 40 years.

Internet skeptics are also quick to point out that Paul R. Allen wasn’t instrumental in the $3 billion fraud scheme. These skeptics are the problem and reason behind the outcry about these two men. Do we really believe that the fact Roy Brown “seemed armed” to the teller is decisive—no matter what the difference is between $100 and $3 billion? No matter whether or not there were mitigating factors at play—hunger, homelessness, and voluntary surrender?

The huge difference in the punishment for these crimes is due, at least in part, to simple human psychology. In The Life You Can Save, Australian philosopher Peter Singer explored why millions continue to die of preventable disease, malnutrition, and starvation, despite the arsenal of wealth available to solve all of these problems. He attributed it to diffusion of responsibility and cognitive dissonance—in one of the book’s examples, he asks you, the reader, to imagine walking briskly to work in a wool suit. You pass a toddler in a shallow pond, and the toddler appears to be drowning. No one else is in the vicinity. In that moment, almost anyone would run into the pond, save the child, and happily ruin the wool suit and arrive late to work. Then Singer reminds readers: At the same time you are walking to work in a suit, somewhere else in our world, a child is dying of hunger. In fact, Bread for the World estimates, a child dies of hunger every five seconds. Sure, you and I can’t save every single one of those children on our own. But the shocking part is that chances are high that you and I have never even tried to save one of them.

We can feel robbery. We can feel someone taking $100 out of our hand and we can picture the teller terrified and faced with what appears to be a gun. We have a lot of trouble feeling an elaborate, unfamiliar $3 billion tax scheme, where a simple click of a mouse can imperceptibly bankrupt someone and the “crook” sits harmlessly at a mahogany desk.

Empathy and action have a lot to do with visibility. As a result, we often fail to empathize with the little people who suffer from the big schemes: the employee with dashed hopes of retirement, the mother who fruitlessly cut corners for her child’s education, the family who must now depend upon food stamps.

This dependency we have on feeling is at the root of refusing to admit that these stories represent an injustice. Our criminal system is littered with sweeping laws enacted after public outcries (e.g. the AEDPA enacted in the wake of the Oklahoma City Bombing), but what that system needs now is reform from the head, not from the heart.

Note: There was a typo in the first version of this post indicating Paul R. Allen was sentenced to 3 months in prison. It has been corrected to reflect the sentence was 40 months. I sincerely apologize for the error. -Suzy Marinkovich